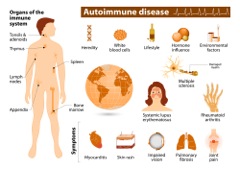

A study released by scientists from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania have discovered a way to delete the subset of antibody-making cells that cause an autoimmune disease without harming the rest of the immune system. Scientists believe the study has the potential for future treatment of autoimmunity and related conditions.

A study released by scientists from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania have discovered a way to delete the subset of antibody-making cells that cause an autoimmune disease without harming the rest of the immune system. Scientists believe the study has the potential for future treatment of autoimmunity and related conditions.

Current therapies for autoimmune disease, such as steroids like prednisone and the cancer-suppression drug, rituximab, suppress large parts of the immune system, leaving patients vulnerable to potentially fatal infections and other cancers.

The specific disease that Penn researches studied, called pemphigus vulgaris (PV), is a condition where a patient’s own immune cells attack a protein called desmoglein-3 (Dsg3) that normally binds skin cells together. According to the study, the Penn researchers demonstrated their new technique by successfully treating an otherwise fatal autoimmune disease in a mouse model, without apparent “off-target effects,” which could harm healthy tissue. The results were published in an online First Release paper on June 30, 2016 in Science.

“This is a powerful strategy for targeting just autoimmune cells and sparing the good immune cells that protect us from infection,” co-senior author Aimee S. Payne, MD, PhD, an Albert M. Kligman Associate Professor of Dermatology, wrote in a statement released by the Perelman School of Medicine.

Payne and her co-senior author, Michael C. Milone, M.D., Ph.D., an assistant professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, adapted the deletion technique from a promising anti-cancer strategy by which “T cells,” which are an integral part of the human immune system that help fight disease, are engineered to destroy malignant cells in certain leukemias and lymphomas.

“Our study effectively opens up the application of this anti-cancer technology to the treatment of a much wider range of diseases, including autoimmunity and transplant rejection,” Milone wrote of their findings.

While not citing the specifics of why pemphigus vulgaris was specifically chosen by researchers, the condition occurs when a patient’s antibodies attack molecules that normally keep skin cells together. When left untreated, PV leads to extensive skin blistering and is almost always fatal, but in recent decades the condition has been treatable with broadly immunosuppressive drugs such as prednisone, rituximab and mycophenolate mofetil, also known by its retail name, CellCept.

Researchers said their plan now was to test the treatment in dogs, which can also develop PV, and often die from the disease. “If we can use this technology to cure PV safely in dogs, it would be a breakthrough for veterinary medicine and would hopefully pave the way for trials of this therapy in human pemphigus patients,” Payne wrote in Science.